Source Credit : Portfolio Prints

Background

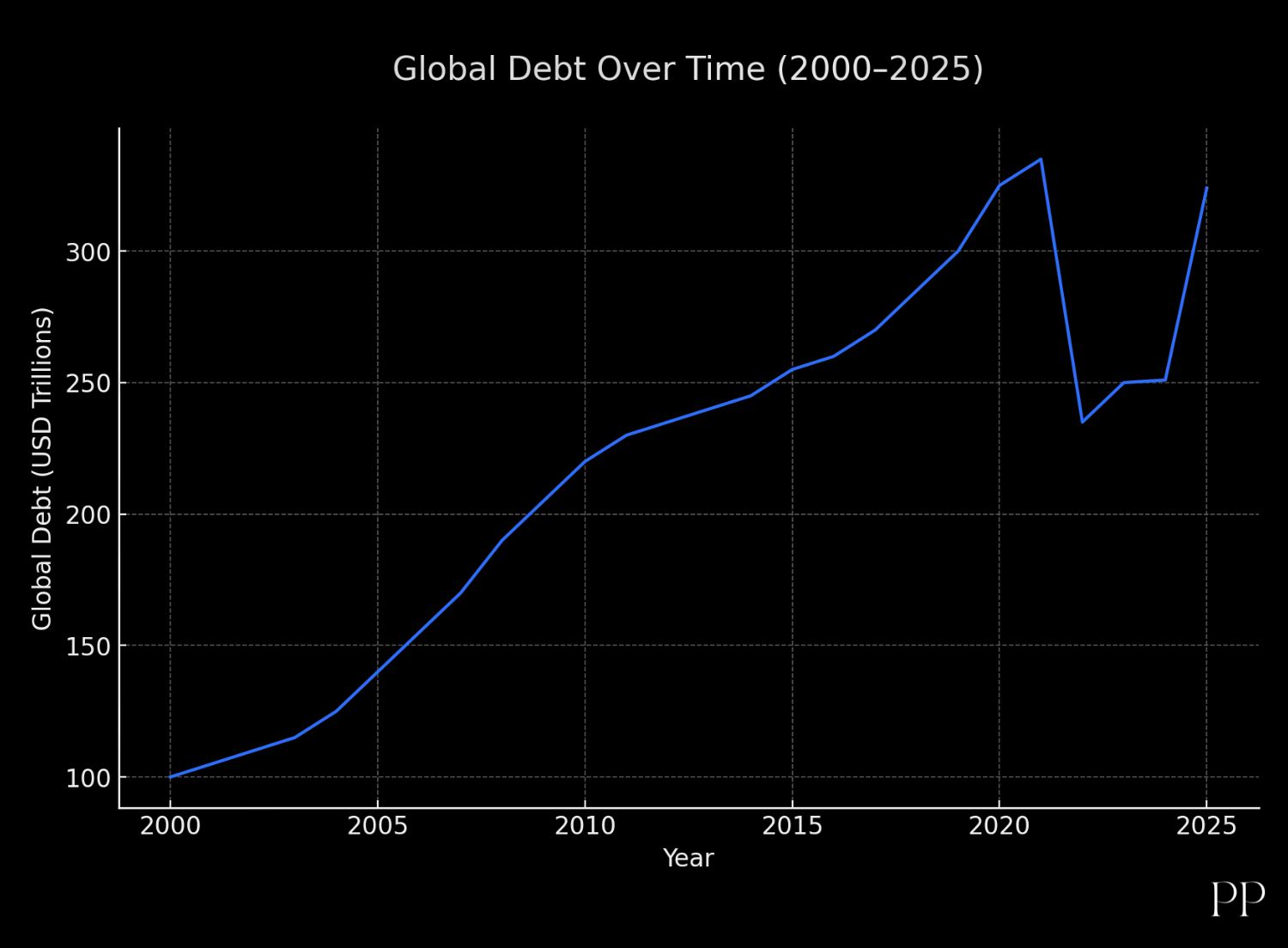

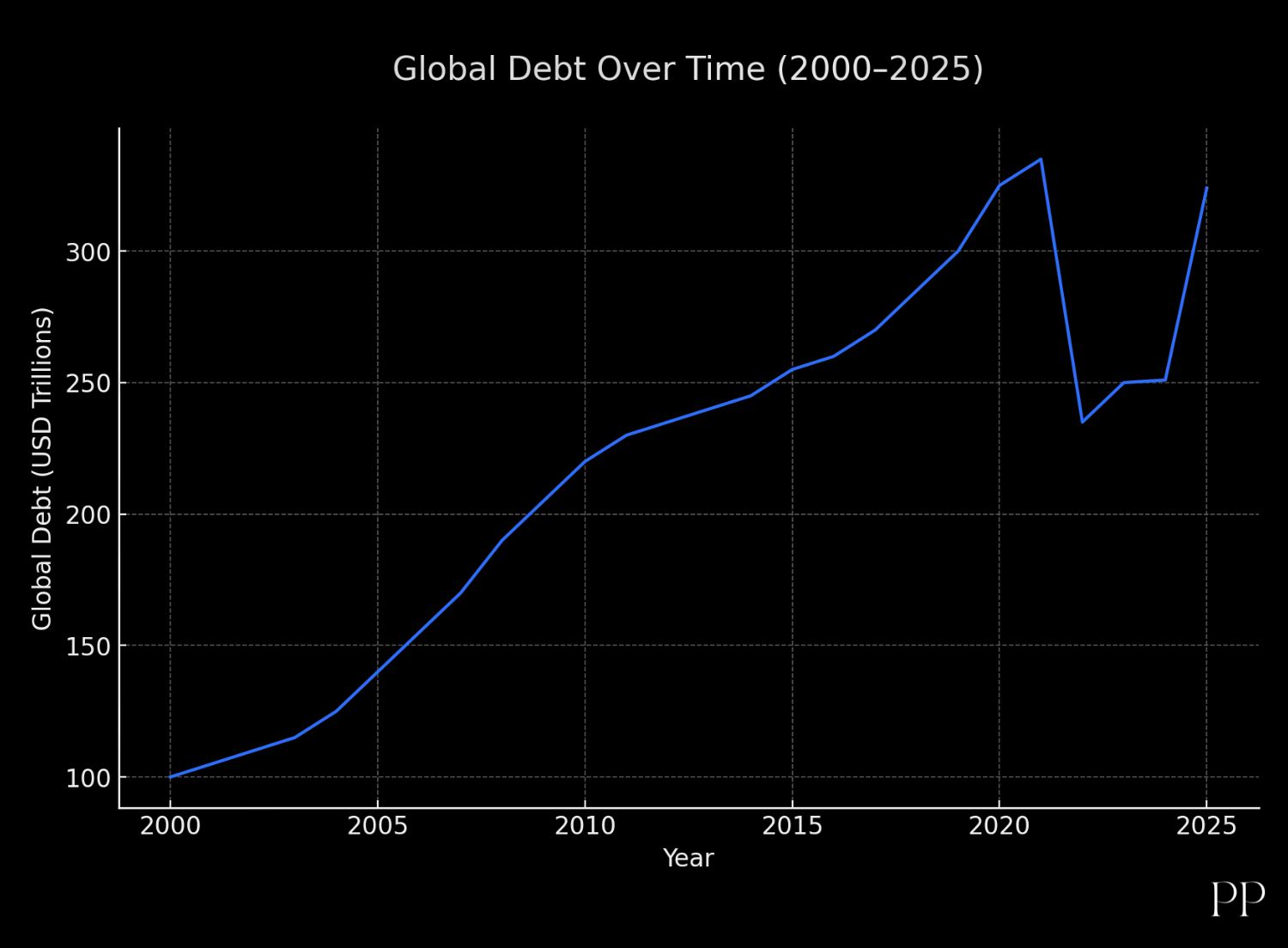

In recent months, global debt levels have surged to heights previously deemed unthinkable — prompting serious concern among economists, investors, and policymakers. The rise reflects not only governments’ post-pandemic heavy borrowing, but also increased corporate and household leverage worldwide. The consequences are likely to ripple across markets, economic growth, and social welfare for years to come.

Where We Stand: Debt Has Reached Historic Highs

- According to the Institute of International Finance (IIF), global debt reached nearly US$ 346 trillion by the end of the third quarter of 2025 — roughly 310% of global GDP.

- The increase since the start of the year alone is reported at US$ 26.4 trillion.

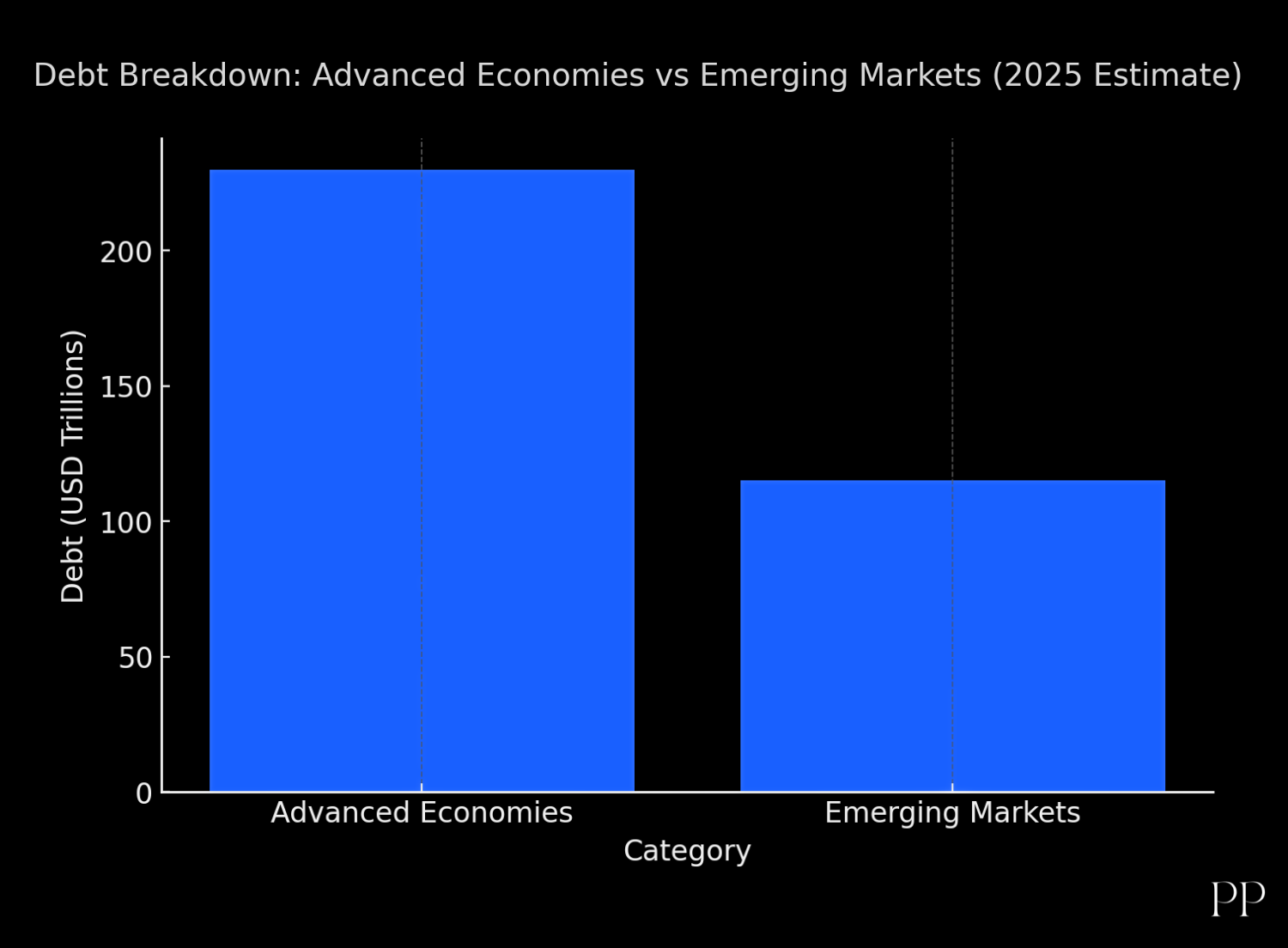

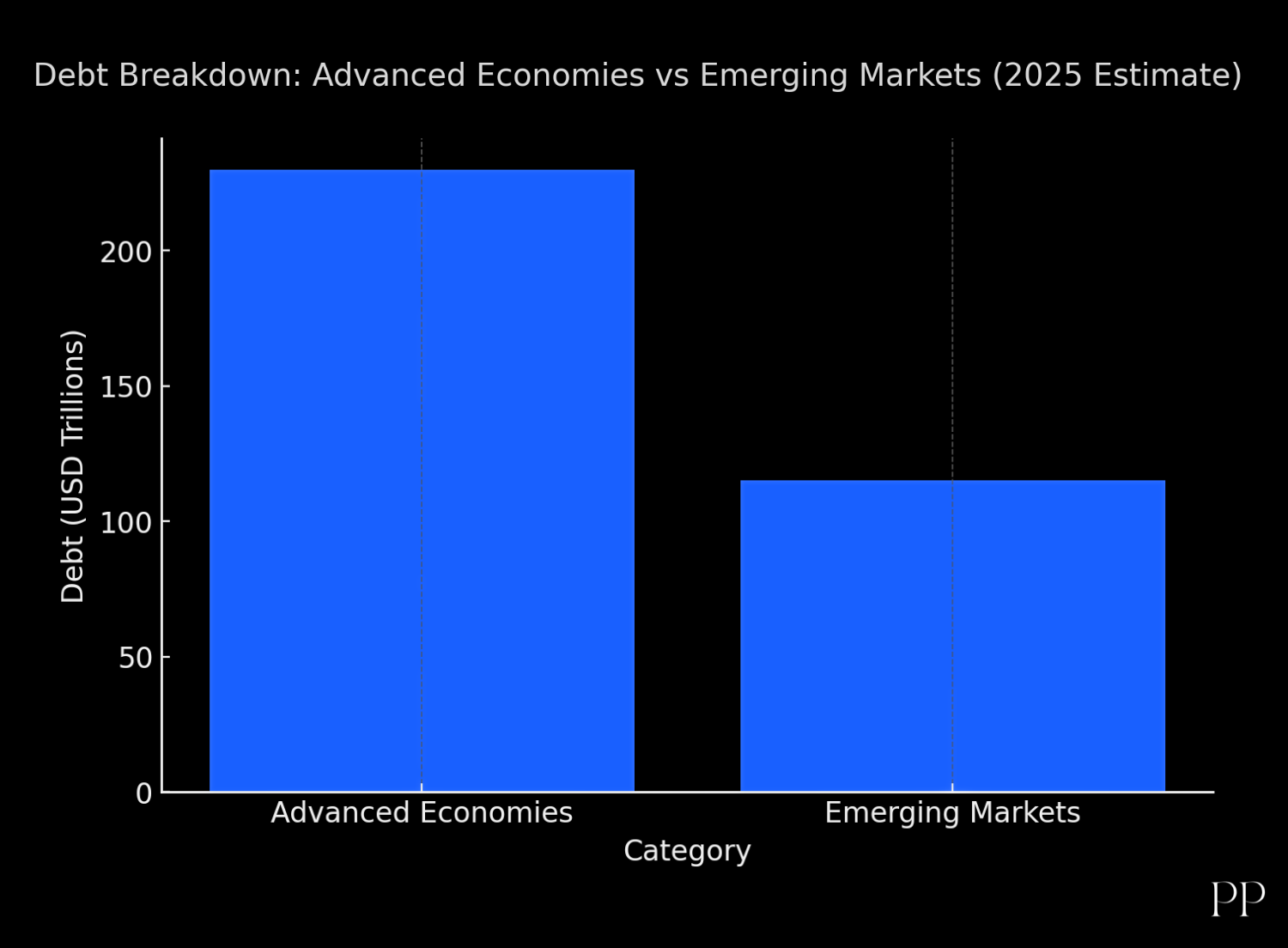

- This build-up is driven primarily by state borrowing — particularly in mature, developed economies. Debt among advanced economies is estimated at around US$ 230.6 trillion, while emerging markets account for over US$ 115 trillion.

- On a broader scale, a recent update from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) finds total world debt remains elevated — above 235% of global GDP.

In short: the world is now more indebted than ever before — by a wide margin.

| Year |

Estimated Global Debt (USD Trillion) |

Reason / Context |

| 2008 |

190 |

Global Financial Crisis → governments borrow heavily for bailouts |

| 2020 |

325 |

COVID-19 pandemic → massive government stimulus + corporate borrowing |

| 2022 |

235 |

IMF revision after methodology update (slightly lower number vs IIF) |

| 2025 |

324 |

IIF reports surge due to: renewed borrowing + currency effects + rate cuts |

Why the Debt Surge Happened

Several factors have converged to push global debt to record highs:

- Post-pandemic fiscal and stimulus measures pushed many governments into deeper borrowing to support economies during lockdowns and recovery.

- Central banks in many advanced economies have recently eased policies again, reducing borrowing costs and encouraging fresh government and corporate issuance. This helped fuel the surge.

- For companies and households worldwide, credit remains broadly accessible — continuing long-term trends of leveraging to fund investment, expansion, or consumption.

- In emerging and developing countries, debt levels rose not only from new borrowing but from currency effects: weaker dollar valuations inflated the dollar-value of many foreign-currency debts.

Risks & What It Means for Markets, Economies, and Ordinary People

Increased Vulnerability to Shocks

High debt — especially when paired with rising interest rates — makes both countries and companies more vulnerable to economic shocks. Servicing costs could swiftly rise, leaving less room for public services, investment, or growth initiatives.

The growing debt burden can force central banks to choose between supporting growth and controlling inflation — raising fears of a return to “fiscal dominance,” where monetary policy becomes hostage to debt servicing needs.

Pressure on Growth & Investment

Much of this new borrowing is meant to support recovery or short-term needs; moving forward, the ability to invest in infrastructure, climate action, or social welfare may be constrained. The recent Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) Global Debt Report warns that refinancing costs are rising, and governments may struggle to shift from debt-financed recovery toward investment-led growth.

If economic growth remains sluggish, high debt levels can become a drag — public and private debts may weigh on productivity and long-term development.

Market Instability — Especially in Bond & Credit Markets

With record-high sovereign and corporate borrowing, bond markets are becoming more sensitive to interest-rate moves and global economic sentiment: small shifts can trigger large waves of refinancing risk.

Investors could become more selective, pushing up yields (i.e., cost of borrowing) — especially for lower-rated borrowers or riskier emerging economies.

For companies with high leverage, slow revenue growth or rising borrowing costs can create liquidity stress — possibly leading to defaults, layoffs, and reduced corporate investment.

Economic Inequality & Social Impact — Especially in Vulnerable Countries

For low- and middle-income countries, heavy debt burdens often translate into less spending on essentials such as health, education, and infrastructure — undermining development and worsening inequality. Recent data from the World Bank show that between 2022–2024, developing nations paid out US$741 billion more in debt servicing than they received in fresh financing — the largest gap in 50 years.

In many countries, finishing projects or funding public welfare programs may become harder if debt servicing keeps eating into budgets.

For citizens, this could mean slower economic growth, reduced public services, and — depending on macroeconomic policy — potential tax hikes or spending cuts.

What Could Happen Next — Scenarios to Watch

| Scenario |

Triggers |

Possible Outcome |

| Managed Fiscal Adjustment |

Governments use breathing room in bond markets to restructure debt and focus on productive investments |

Debt stabilizes or slowly declines; sustainable growth resumes |

| Market Tightening & Rate Hikes |

Rising inflation or interest rates, combined with cautious investors |

Higher bond yields, tougher borrowing conditions, defaults or restructuring for weaker borrowers |

| Debt-Driven Economic Slowdown |

High debt crowds out investment; refinancing stress limits government spending |

Slow growth, reduced public services, increasing inequality and social strain |

| Financial Crisis in Vulnerable Economies |

External shocks (commodity price collapse, currency depreciation, interest surge) |

Debt defaults or restructuring; economic instability and social disruption in emerging nations |

Key Takeaways for Policymakers, Markets — and You

- Policymakers should treat high debt as more than a headline — they need to prioritize debt sustainability, investing in growth-generating sectors rather than short-term bailouts or consumption.

- Investors and markets need to reassess risk: high yields may look tempting, but debt-heavy borrowers (governments or companies) may become fragile if interest rates or conditions worsen.

- For people in emerging economies (like India), the debt wave abroad can translate into higher import costs, tighter capital flows, and potential volatility — underlining why growth should come with caution and resilience.

- Finally — with high global debt and several risks aligned (slowing growth, geopolitical tensions, climate change) — long-term economic stability is not guaranteed. What happens next depends heavily on policy decisions, global cooperation, and market discipline.

Summary

the record-high global debt level is more than a number — it’s a warning sign. Without careful management, it could hamper growth, destabilize economies, and deepen inequality. But with prudent fiscal policies and smarter investment choices, it could also mark a turning point: a chance to reorient global economies toward sustainable, equitable growth.